Is NAFTA still relevant in 2017?

by Brian Romer (feat. Eric Miller)

Reuters

September 6, 2017

Good neighbors

NAFTA came into force in 1994 and built on existing trade between Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. The deal focused on eliminating trade tariffs between the countries, particularly in the agriculture, textiles and automobile manufacturing industries. It also sought to protect intellectual property, establish dispute-resolution mechanisms and, through side agreements, implement labor and environmental safeguards.

Automotive trade

From Mexico’s first automobile plant in 1925, through the debt crisis of 1982 – after which Mexico changed policy to boost exports – to the implementation of NAFTA in 1994, Mexico has become prime territory for the automotive industry.

In 2015, the Automotive sector represented more than 3% of Mexico’s GDP, ending the year with a trade surplus of about US$50 billion, domestic sales above 1.3 million vehicles and production of 3.4 million vehicles. Employing about 1.7 million people, Mexico is on track to reach Japan as the No. 2 vehicle supplier to the U.S. market.

Currently, Mexico has eight automotive producers operating within its borders: Ford, Chrysler, GM, VW, Toyota, Nissan, Mazda and Honda. Marcos Piacitelli, Free Trade Agreement (FTA) specialist at Thomson Reuters, says, “Mexico stands out for its geographic location as a close door to the U.S. car market with very cheap labor in comparison to other countries, a good reputation for producing with excellent quality, great production efficiencies, and several public and tax incentives to promote growth and development … a key to Mexico’s standout automotive success is an extensive network of FTAs, which provides the sector with access to 45 countries.”

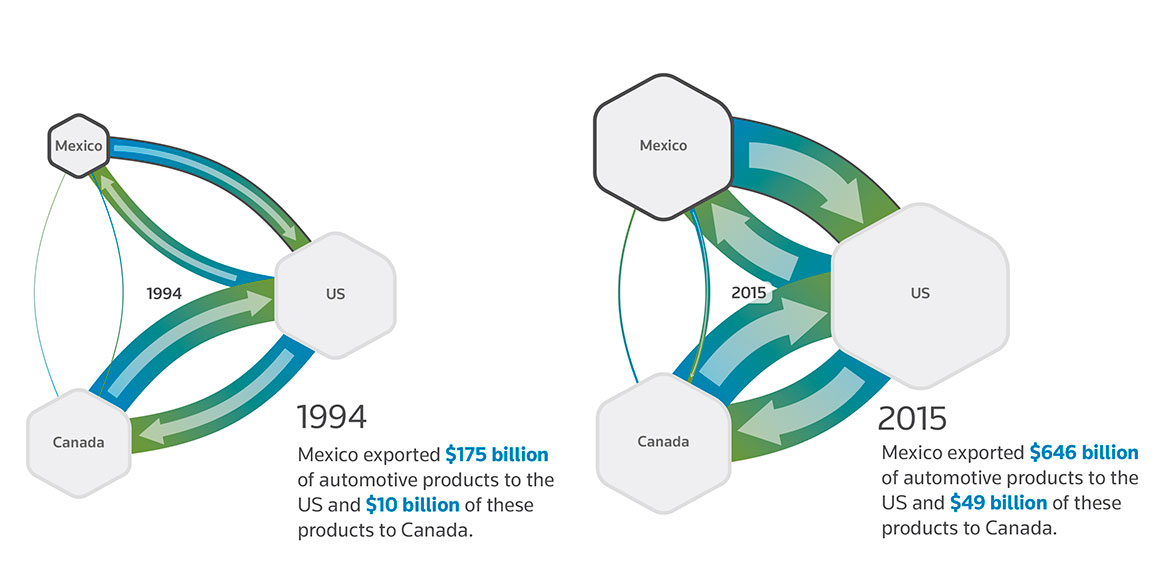

Visualizing the UN Comtrade data lets us observe the dramatic shift in automotive trade over 25 years. Mexico’s exports to the U.S. grew almost sevenfold, recovering strongly from a big crash in the 2008-2009 recession. And although the U.S. appetite for automotive imports is much larger than what NAFTA countries can supply, the U.S. has remained a committed partner to Mexico and Canada.

Automotive trade in NAFTA is not composed simply of one country exporting vehicles to another. For some products and components, trade threads its way back and forth in multiple, cross-border pathways. Auto parts can circulate between U.S., Mexican and Canadian factories, being built upon and enhanced at each stage, before the end product vehicle is finally assembled.

A metric of participation

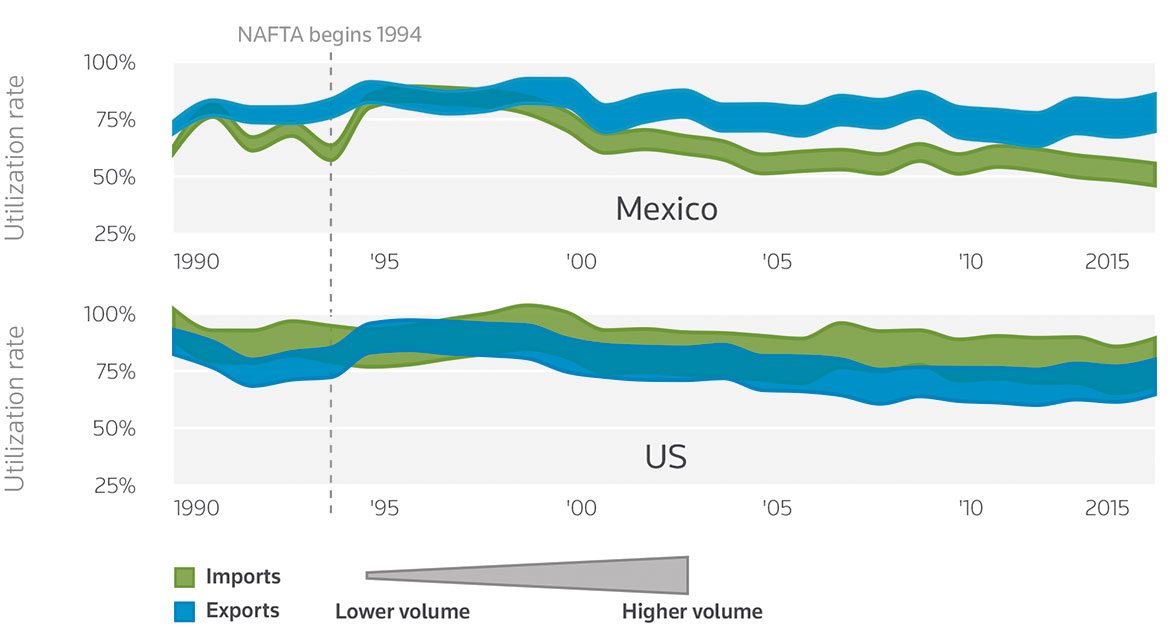

The dollar value of automotive trade over time is only one metric of effectiveness. Another is how efficiently each country has utilized NAFTA. For example, each year Mexico has the opportunity to export cars to nearly any country in the world. How often does it choose to export to NAFTA countries?

By comparing intra-NAFTA trade to extra-NAFTA trade – per country, per commodity – we can derive a utilization metric and see how each country has performed. The plots in Chart 1 show an aggregate of automotive commodities such as passenger cars, transport vehicles and auto accessories at two points in time. Each line in Chart 2 plots this utilization score horizontally, over time. The thickness of the line indicates the relative volume of trade.

Chart 1: NAFTA Trade Flows – Automotive

Thomson Reuters Global Trade Analysis, Thomson Reuters Labs

Thomson Reuters Global Trade Analysis, Thomson Reuters Labs

Chart 2: NAFTA Participation – Automotive

Utilization and volume of trade among NAFTA countries: Mexico and the US, automotive commodities

Thomson Reuters Global Trade Analysis, Thomson Reuters Labs

Thomson Reuters Global Trade Analysis, Thomson Reuters Labs

Mexico is consistently strong on exports and less so on imports, with its volume of trade growing steadily over the decades. The U.S. displays both high utilization and high volume for automotive imports and exports.

Oil and energy trade

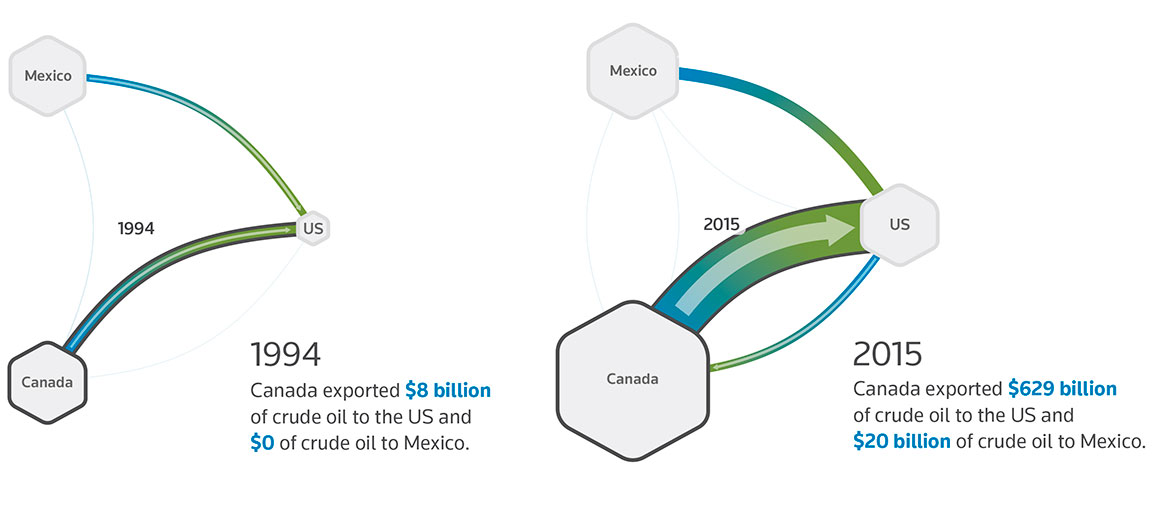

Canada’s oil exports to the US grew from $8 billion since NAFTA’s inception to a high of $86 billion in 2014, yet plummeted to $50 billion in 2015.

Joshua Starnes, director of Oil Research, Americas, Thomson Reuters, argues that the recent struggles of Canadian oil exports are not the problem of U.S. fracking so much as the combination of fracking and U.S. oil exports.

“When U.S. oil exports were banned, U.S. fracking was a boon to Canadian exporters as Canadian heavy crude was the perfect complement for US light shale crude to create the medium grades US refineries need. The lifting of the US ban has allowed desirable light crude to flow out of the US, decreasing the need for Canadian heavy crude in the US refining complex. Canada now has to face increased competition on the world market for its heavy crude,” which can be seen in Chart 3 below.

Chart 3: NAFTA Trade Flows – Crude Oil

Thomson Reuters Global Trade Analysis, Thomson Reuters Labs

Thomson Reuters Global Trade Analysis, Thomson Reuters Labs

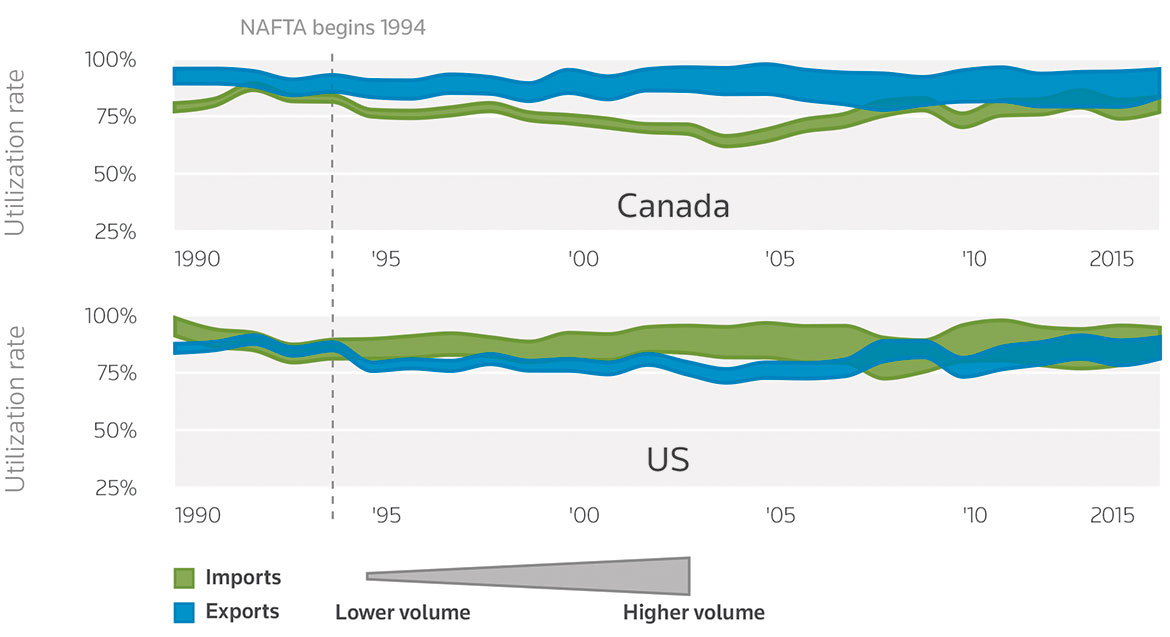

The utilization chart (Chart 4) shows Canadian and U.S. participation rates for an aggregate of several energy commodities including crude oil, natural gas and coal. The trade flow chart focuses on crude oil only.

Chart 4: NAFTA Participation – Energy

Utilization and volume of trade among NAFTA countries: Canada and the US, energy commodities

Thomson Reuters Global Trade Analysis, Thomson Reuters Labs

Thomson Reuters Global Trade Analysis, Thomson Reuters Labs

Difficult by design

There are many reasons. The usual standard that must be met is that a product must be “substantially transformed” within the region or party country to be considered qualifying under the agreement. The standards of “substantial transformation” differ from FTA to FTA and from product to product.

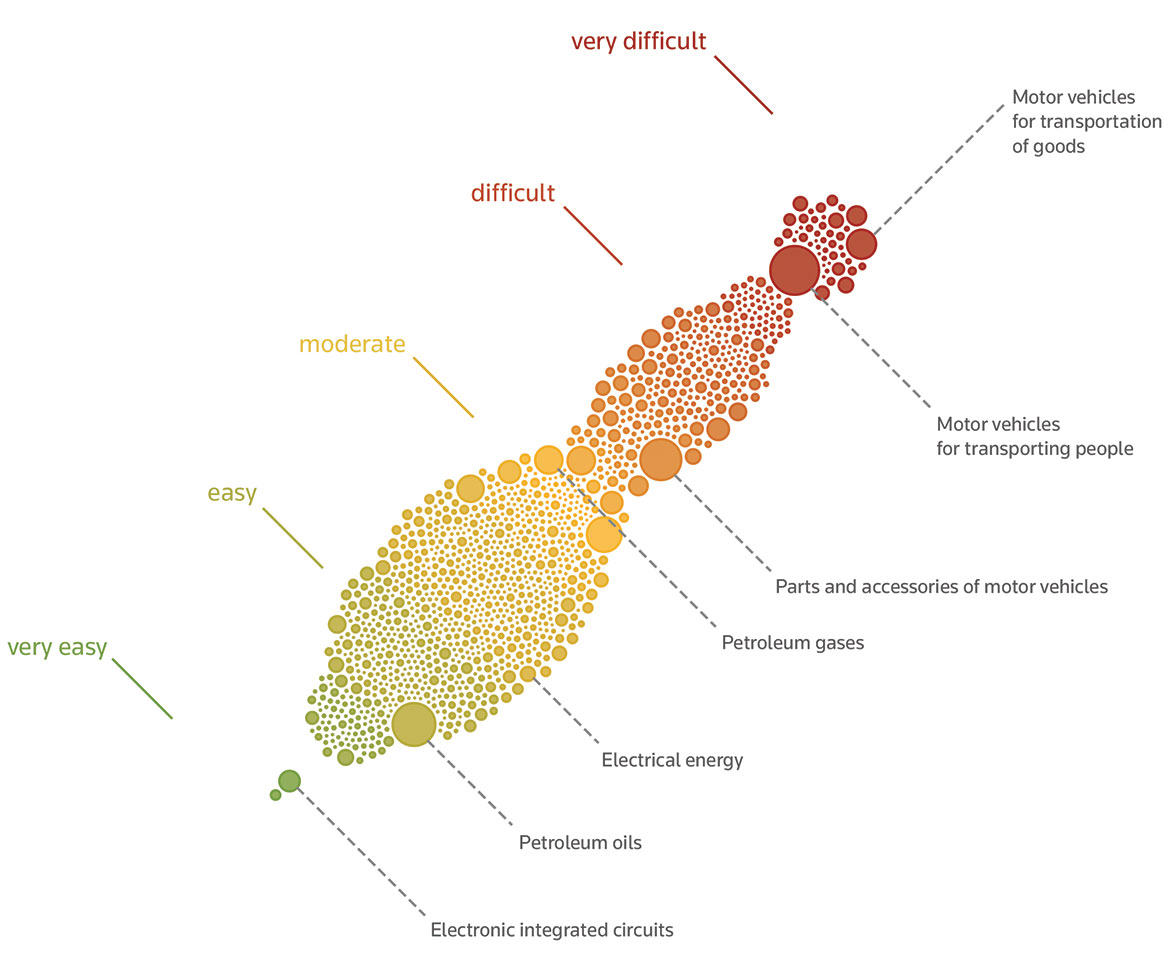

There are two main ways that a rule of origin may be difficult to comply with: due to the level of “transformation” required, or due to the complexity involved in interpreting and applying the rules. Thomson Reuters Global Trade created a difficulty scale which incorporates both of these definitions and scored every commodity traded in NAFTA.

Products with complex manufacturing processes may require very detailed rules of origin to establish the “substantial transformation” standard. Also, participating countries have an interest in ensuring they aren’t granting duty-free status to products that don’t warrant it, thereby missing out on duty revenue. Finally, a rule may be difficult to comply with if a government identifies that industry as one which should be protected from international competition.

The following Chart 5 plots over 1,200 commodities according to the ease or difficulty of rule compliance in NAFTA, as well as by their annual average volume of trade within NAFTA.

Chart 5: NAFTA Commodity Compliance Complexity

Over 1,200 commodity types are scored on the ease or difficulty of complying with NAFTA rules

Thomson Reuters Global Trade Analysis, Thomson Reuters Labs

Thomson Reuters Global Trade Analysis, Thomson Reuters Labs

Most products fall on the moderate-to-easy part of the scale. Although there are many “difficult” commodities, most of these are not traded at high volume. The exception is automotive. Energy commodities fall in the easy-to- moderate spectrum. Among the easiest to trade are electronic integrated circuits.

Strong history, uncertain future

The data confirm the picture of NAFTA as a long-standing and multilaterally beneficial FTA, especially for many automotive and energy products. The scale and growth in the amount of trade, as well as the metric of participation, are high in these areas, despite structural difficulty of complying with commodity rules.

What’s next for NAFTA? Eric Miller, president of Rideau Potomac Strategy Group, says, “Much policy change is on the horizon for the North American auto industry. Companies would be wise to develop their own NAFTA re-negotiation strategies with a view to advancing their interests. It is rare that the rules governing commerce across an entire region are re-made. Assemblers and suppliers alike must seek to ‘own’ the changes to come and ensure that the new post-NAFTA framework is ultimately workable and even advantageous.”

Be the first to comment

Sign in with